Contrary to popular belief, improving motor skills isn’t about more practice or just ‘more sleep’; it’s about actively enhancing the brain’s nightly ‘pruning’ process during REM cycles.

- Your brain doesn’t just store movements; it actively deletes 40% of new neural connections each night to strengthen the remaining, essential ones.

- Common habits like a late-afternoon coffee or an abrupt alarm are not minor inconveniences; they are direct attacks on this critical REM-driven consolidation process.

Recommendation: Shift your focus from total sleep hours to protecting and extending your REM cycles by managing your neurochemical environment before and during sleep.

As a technical athlete, you’ve felt the frustration. You spend hours drilling a new takedown, a complex gymnastic sequence, or a difficult chord progression. It feels almost perfect in the gym, but the next day, it’s gone. The fluidity is lost, the details are fuzzy, and it feels like you’re starting from scratch. You’ve been told to “sleep on it,” but what if the very way you sleep is sabotaging your progress?

The common advice—get eight hours, avoid blue light, keep a routine—is well-meaning but incomplete. It treats sleep as a passive recovery state. For an athlete focused on skill acquisition, this view is dangerously simplistic. The real breakthroughs in motor learning don’t happen in the gym; they happen in the intricate, fragile, and deeply misunderstood phase of your sleep known as the REM cycle.

This is where the brain acts not as a passive storage device, but as an expert sculptor. It chisels away at the day’s experiences, discarding irrelevant neural “noise” to fortify the “signal” of the skills you want to master. This article moves beyond generic sleep hygiene. We will explore the neurobiological mechanisms of REM sleep and provide a performance-focused protocol to manipulate your sleep architecture. You will learn not just *that* REM is important, but *how* to protect and extend it to accelerate the consolidation of complex movement patterns.

This guide will deconstruct the key factors that enhance or destroy your brain’s ability to learn while you sleep. We will examine the hidden costs of common habits, the true meaning behind your dreams, and the scientifically-backed strategies to turn your sleep into your most powerful training tool.

Summary: A Neuro-Performance Protocol for Motor Learning

- Why You Keep Forgetting New Techniques Despite Practice If You Cut REM Short?

- How a 2 PM Coffee Reduces Your REM Cycle Duration by 20%?

- Dreaming Vividly vs Blackout Sleep: Which Indicates Better Mental Restoration?

- The “Sleep Drunkenness” Effect of Waking Up via Loud Alarm During REM

- Why Uberman Sleep Schedules Destroy Cognitive Function Long-Term?

- Lion’s Mane vs Psilocybin Microdosing: Which Is Safer for Daily Focus?

- Why Hitting a Plateau Is a Necessary Part of the Adaptation Cycle?

- Active Cardiovascular Recovery: How to Flush Lactate Without Adding Fatigue?

Why You Keep Forgetting New Techniques Despite Practice If You Cut REM Short?

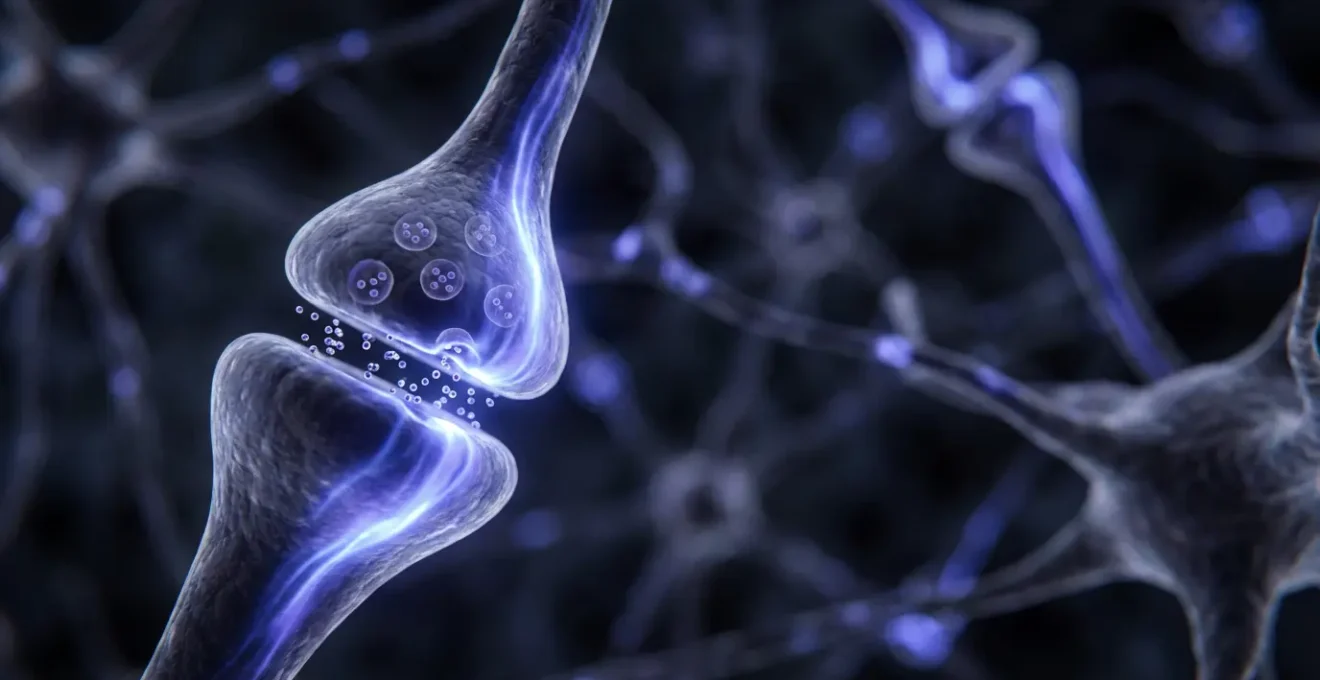

The feeling of a new skill “disappearing” overnight is not a failure of memory, but a failure in the brain’s nightly optimization process. During the day, every attempt at a new movement creates a flurry of new neural connections, or dendritic spines, in your motor cortex. Your brain is essentially ‘taking notes’ in a messy, redundant way. The real learning happens when you sleep, specifically during REM, which acts as a sophisticated editor. It’s a process of synaptic pruning, and it is ruthlessly efficient.

This isn’t about simple storage. Instead, REM sleep’s job is to increase the signal-to-noise ratio of your motor skills. It strengthens the critical, efficient pathways (the “signal”) that lead to a successful movement while actively eliminating the weak, unnecessary, and incorrect ones (the “noise”). Groundbreaking research published in Nature Neuroscience demonstrates that REM sleep selectively eliminates around 41% of these newly formed connections, making the remaining ones stronger and more permanent. When you cut REM short, you interrupt this editor. Your brain is left with a noisy, inefficient network of connections, which manifests as clumsiness and forgetting the next day.

As the visualization shows, REM sleep doesn’t just save your work; it improves it. It transforms a tangled web of potential pathways into a clean, powerful superhighway for that specific skill. Without sufficient REM, you aren’t consolidating a new technique; you are just accumulating neurological noise. While non-REM deep sleep helps in “extracting the gist” of a task, it’s the subsequent REM cycles that refine and solidify the precise motor pattern. For a technical athlete, this distinction is everything.

How a 2 PM Coffee Reduces Your REM Cycle Duration by 20%?

That afternoon coffee you rely on to power through a late training session has a hidden neurological cost that directly impacts your ability to learn. The culprit is caffeine, a molecule that bears a striking resemblance to adenosine, a neurotransmitter that builds up in your brain throughout the day and signals sleepiness. Caffeine works by blocking adenosine receptors, essentially putting a piece of tape over your brain’s “fatigue gauge.” While this provides a temporary boost in alertness, the cognitive residue lasts far longer than the feeling of focus.

Caffeine has a half-life of about 5-6 hours, meaning that if you drink a coffee at 2 PM, a significant portion of that caffeine is still actively blocking adenosine receptors when you’re trying to sleep at 10 PM. This chemical interference disrupts the natural progression of your sleep stages, a process known as sleep architecture. The brain struggles to transition smoothly into deeper stages of sleep and, most critically for motor learning, it significantly suppresses the duration and quality of REM sleep.

It’s not just a feeling of being less rested; it’s a measurable deficit in neuro-consolidation. A recent 2024 randomized clinical crossover trial found that even moderate caffeine intake six hours before bed can significantly disrupt sleep and reduce total REM time. For an athlete, a 20% reduction in REM isn’t just a number; it’s a 20% reduction in the brain’s ability to prune, refine, and consolidate the very skills you spent all day practicing. You’re effectively paying for a few hours of afternoon focus with the currency of next-day performance.

Dreaming Vividly vs Blackout Sleep: Which Indicates Better Mental Restoration?

Many athletes chase the “blackout” sleep—a deep, dreamless state they perceive as the ultimate form of rest. However, from a neuro-performance perspective, this is a misunderstanding of what constitutes effective recovery. An absence of dream recall doesn’t necessarily mean better sleep; in fact, consistently vivid and memorable dreams are a strong indicator that your brain is successfully engaging in the critical work of REM sleep. Dreaming is the subjective experience of your brain’s memory consolidation and emotional regulation processes at work.

Sleep isn’t a monolithic state. It’s a dynamic cycle between two very different but equally important phases: Non-REM (which includes deep or slow-wave sleep) and REM sleep. Slow-wave sleep is for physical restoration and initial memory filing. This is when the brain shows immense neural plasticity, deciding what information from the day is important enough to keep. As Brown University neuroscience research reveals that non-REM sleep is about strengthening new memories, REM sleep is about integrating them. It’s during REM that the cerebellum and cortical motor areas become highly active, replaying and refining motor sequences.

Vivid, even bizarre, dreams are often the hallmark of this process. The brain is taking the new motor skill, stripping it of its original learning context, and connecting it to your existing network of movements. A “blackout” sleep might indicate excellent slow-wave sleep, which is crucial for physical recovery, but a lack of dream recall could also suggest suppressed or fragmented REM cycles. For a technical athlete, the ideal night involves both: deep, restorative slow-wave sleep followed by robust, long periods of REM sleep, rich with the dreams that signal your brain is hard at work turning practice into permanent skill.

The “Sleep Drunkenness” Effect of Waking Up via Loud Alarm During REM

The jarring blast of a loud alarm clock might feel like a necessary evil, but it’s one of the most destructive things you can do to your cognitive performance. When an alarm yanks you from the middle of a deep REM cycle, you don’t just wake up; you experience a state of severe cognitive impairment known as sleep inertia or “sleep drunkenness.” This isn’t just grogginess—it’s a measurable neurological phenomenon where parts of your brain are still effectively asleep.

During REM, your brain is highly active, consolidating memories and processing emotions. The prefrontal cortex—the hub of decision-making, problem-solving, and emotional regulation—is temporarily offline. An abrupt awakening forces this region to reboot under duress. Neuroscience research indicates it can take 30-60 minutes for the prefrontal cortex to fully come back online after being violently interrupted during REM. For that first hour, your reaction time is slower, your judgment is impaired, and your ability to perform complex tasks is significantly reduced. You’re operating with only a fraction of your mental capacity.

This cognitive fog, as depicted in the image, is the direct result of a fragmented awakening. Instead of a smooth, natural transition from sleep to wakefulness guided by your circadian rhythm, the loud alarm causes a system crash. For an athlete, starting the day with an hour of impaired cognitive function is a significant handicap. It not only affects your morning training but also sets a negative tone for your entire day’s focus and learning capacity. The goal should be to wake up *at the end* of a sleep cycle, during a lighter stage of sleep, not to be ripped from its deepest and most crucial phase.

Why Uberman Sleep Schedules Destroy Cognitive Function Long-Term?

In the quest for productivity, some athletes are tempted by polyphasic sleep schedules like the “Uberman” method, which involves taking six 20-minute naps throughout the day. The theory is to train the brain to enter REM sleep immediately, thus capturing its benefits in short bursts. However, this approach is based on a fundamental misunderstanding of sleep architecture and is disastrous for long-term cognitive function and skill acquisition.

A healthy, natural sleep pattern is monophasic for a reason. Each full sleep cycle is a carefully orchestrated 90-minute sequence: transitioning from light sleep to deep slow-wave sleep (SWS), and finally into REM. SWS is crucial for physical repair and clearing metabolic waste, while REM is for neuro-consolidation. The Uberman schedule attempts to bypass the other stages entirely, which is not only impossible to sustain but also neurologically destructive. By fragmenting sleep into tiny, unnatural chunks, you deprive your brain of the essential deep SWS it needs for basic maintenance. This leads to a build-up of metabolic byproducts and a massive sleep debt that no amount of REM “hacking” can repay.

Furthermore, while the brain may adapt by initiating REM faster under extreme deprivation, this is a stress response, not an optimization. You are sacrificing the holistic, sequential process of a full sleep cycle for a desperate, fragmented version that misses key components. The brain needs the full 90-minute narrative. As sleep science experts emphasize, the interplay between stages is key:

REM sleep prunes newly formed postsynaptic dendritic spines of layer 5 pyramidal neurons in the mouse motor cortex during development and motor learning. This REM sleep-dependent elimination of new spines facilitates subsequent spine formation and also strengthens and maintains newly formed spines, which are critical for neuronal circuit development and behavioral improvement after learning.

– Li, W., Ma, L., Yang, G. et al., Nature Neuroscience – REM sleep selectively prunes and maintains new synapses

This intricate pruning and strengthening process cannot be rushed or compartmentalized into 20-minute windows. Trying to do so is like trying to build a house by only installing windows, ignoring the foundation and walls. The structure will inevitably collapse.

Lion’s Mane vs Psilocybin Microdosing: Which Is Safer for Daily Focus?

In the search for a cognitive edge, many athletes explore nootropics and other compounds to enhance focus and learning. Two popular but vastly different options are Lion’s Mane mushroom and psilocybin microdosing. While both are claimed to improve cognitive function, their mechanisms, legal status, and, crucially, their impact on sleep architecture and learning make them worlds apart, especially for an athlete concerned with safe, consistent performance enhancement.

Lion’s Mane is a legal, edible mushroom that has been used in traditional medicine for centuries. Its cognitive benefits are primarily attributed to its ability to stimulate the production of Nerve Growth Factor (NGF), a protein essential for the growth, maintenance, and survival of neurons. This process supports long-term brain health and neuroplasticity without inducing an altered state of consciousness. Psilocybin, the psychoactive compound in “magic mushrooms,” works differently. As a 5-HT2A receptor agonist, it profoundly alters brain connectivity and perception, even in microdoses. This carries a significant risk of state-dependent learning, where a skill learned in an altered state is difficult to access or replicate when sober.

For an athlete, consistency is key. The goal is to integrate a new skill into your natural, competitive state, not to have it locked behind a chemical key. Lion’s Mane supports the brain’s natural learning processes, while psilocybin creates an artificial one. The following table highlights the critical differences for a performance-focused individual:

| Factor | Lion’s Mane | Psilocybin Microdosing |

|---|---|---|

| Legal Status | Legal supplement worldwide | Controlled substance in most jurisdictions |

| REM Sleep Impact | May increase REM duration (limited studies) | Unclear, anecdotal reports of vivid dreams |

| Mechanism | Boosts Nerve Growth Factor (NGF) | 5-HT2A receptor agonist |

| State-dependent learning | No altered state, integrated learning | Risk of state-dependent memory |

| Safety Profile | High safety, food supplement | Unknown long-term effects, no quality control |

While research into both is ongoing, the choice for a professional athlete is clear. Lion’s Mane offers a safe, legal, and neurologically supportive path to enhancing the brain’s innate ability to learn. Psilocybin, with its legal risks, unknown long-term effects, and potential to create state-dependent skills, represents an unacceptable gamble for anyone whose livelihood depends on reliable, replicable performance.

Why Hitting a Plateau Is a Necessary Part of the Adaptation Cycle?

Every athlete knows the frustration of hitting a plateau. You’re training hard, eating right, but your progress grinds to a halt. This is often seen as a failure, a sign that your training is no longer effective. However, from a neuro-performance standpoint, a plateau is not an obstacle; it’s a biologically necessary consolidation phase. It’s the moment your brain and body pause the acquisition of new information to fully integrate and automate what has already been learned.

When you’re learning a new skill, your brain is in a high-plasticity state, rapidly forming new connections. This is an energy-intensive process. The plateau is your nervous system’s signal that it needs to shift from “learning mode” to “mastery mode.” This is where sleep, particularly REM sleep, becomes the primary driver of progress. The gains are no longer happening in the gym; they are happening in your sleep, as the brain meticulously prunes and strengthens the neural pathways associated with the skill. This sleep-dependent learning is not a minor boost; it’s the main event. Meta-analyses on the subject show a dramatic difference, demonstrating an 18.9-20.5% improvement in motor skill performance after a night of sleep, compared to just 3.9% after the same duration of waking practice.

This period of consolidation is also when your brain integrates the new skill with other, previously mastered movements. It’s building a larger, more complex motor program. Trying to force new information during this phase is counterproductive; it’s like trying to add more bricks to a wall before the mortar has set. The correct response to a plateau is not to train harder, but to train smarter: focus on perfect execution of what you already know, and prioritize your sleep recovery protocol. This allows the brain the time and resources it needs to automate the skill, freeing up cognitive capacity to begin the next learning cycle from a stronger, more stable foundation.

Key Takeaways

- REM sleep is not passive rest; it’s an active ‘sculpting’ process that prunes weak neural pathways to strengthen motor skills.

- Your daily habits, especially caffeine timing and alarm use, have a direct and measurable impact on your sleep architecture and learning capacity.

- True neuro-consolidation requires complete, uninterrupted 90-minute sleep cycles; “hacking” sleep with fragmented schedules is counterproductive.

Active Cardiovascular Recovery: How to Flush Lactate Without Adding Fatigue?

How you cool down after a high-intensity evening workout can make or break your night’s sleep and, consequently, your skill consolidation. Intense exercise floods your muscles with lactate and spikes cortisol and core body temperature—all of which are antagonists to sleep. The common “rest and recover” approach is often too passive. To optimize for sleep, you need a protocol for active cardiovascular recovery that accelerates the removal of metabolic byproducts without adding further stress to the system.

The goal is to transition your body from a sympathetic (fight-or-flight) state to a parasympathetic (rest-and-digest) state as efficiently as possible. A light, active recovery does this far more effectively than collapsing on the couch. Gentle, low-impact movement like walking on a treadmill, stationary cycling with no resistance, or light stretching increases blood flow, which helps to flush lactate from the muscles and transport it to the liver to be converted back into energy. This process reduces muscle soreness and the systemic inflammation that can interfere with sleep onset.

Crucially, this active recovery must be timed correctly and be of low intensity. Sleep hygiene research confirms that high-intensity exercise within 3 hours of bedtime can elevate core body temperature and cortisol, delaying sleep onset. Your cool-down should focus on lowering these metrics. This means finishing your hard training at least three hours before bed and using the final hour for gentle, restorative activities. This deliberate down-regulation signals to your brain and body that the day’s stress is over, creating the ideal neurochemical environment for deep, restorative sleep and robust REM cycles.

Your Post-Training Sleep Optimization Checklist

- End all high-intensity training at least 3 hours before your planned bedtime to allow cortisol to decline.

- In the final 90 minutes before bed, engage in 15-20 minutes of light active recovery (e.g., gentle cycling, slow walking) to help clear metabolic waste.

- Initiate a cool-down by lowering core body temperature with methods like a lukewarm (not cold) shower.

- Dedicate 10 minutes to static stretching or gentle yoga, focusing on deep, diaphragmatic breathing to activate the parasympathetic nervous system.

- Before sleep, review your heart rate variability (HRV) data if you track it. A stable or rising trend indicates good recovery; a sharp drop may signal over-training.

By managing your post-training recovery as meticulously as your training itself, you create a seamless bridge into a night of powerful neuro-consolidation.

Your journey to accelerated skill acquisition doesn’t end with understanding these principles. The next step is to meticulously implement them, transforming your sleep from a passive necessity into your most potent training advantage. Start tonight by auditing your pre-sleep routine and making one specific change based on these protocols.