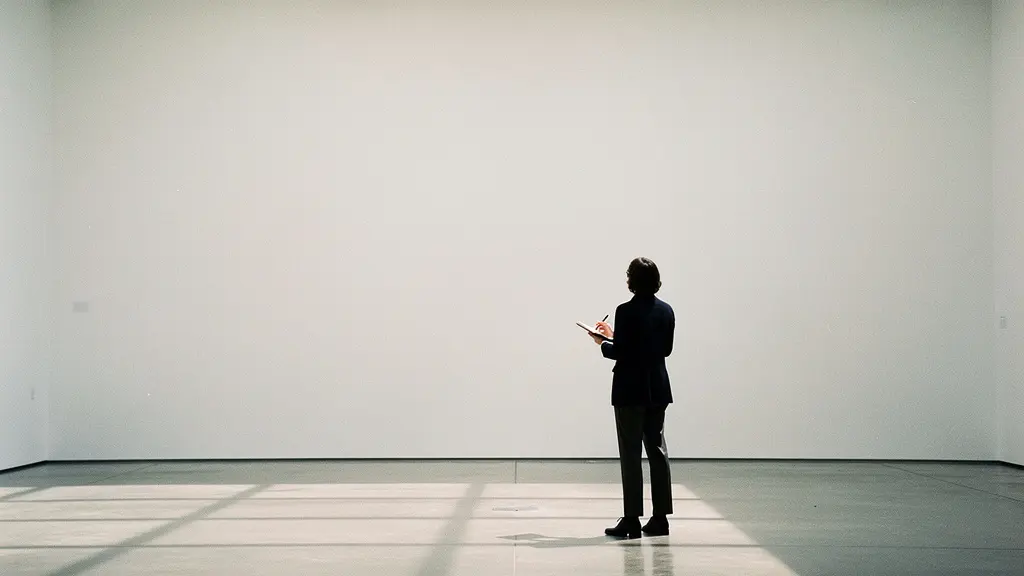

To critique an exhibition like a professional, you must shift your focus from judging individual artworks to decoding the curator’s “visual argument.”

- The placement of art creates a silent narrative, where sightlines and pacing build a specific story.

- Lighting is not neutral; it’s a rhetorical tool used to manipulate your emotional response and dictate focus.

Recommendation: Adopt the “Two-Pass System”—experience the show emotionally first, without reading any text, then return to analyze the curatorial choices and how they shape the meaning.

Most museum visitors find themselves standing before a work of art, armed with a single, frustrating thought: “I like it, but I don’t know why.” Or worse, “I don’t get it.” The common advice is to follow a rigid, academic formula of description, analysis, and judgment, a method that often sterilizes the very soul of the experience. We are told to read the wall text, to understand the artist’s biography, and to place the work in its historical context. While useful, this approach misses the most sophisticated layer of the gallery experience.

A truly professional critique doesn’t just evaluate the art; it evaluates the exhibition itself as a complete, intellectual work. The most powerful element in a gallery is not the painting on the wall, but the invisible hand of the curator who placed it there. What if the key to a deeper understanding wasn’t just in what you see, but in *how* you are made to see it? The secret lies in learning to read the curatorial grammar—the silent, deliberate language of placement, lighting, and sequence.

This guide moves beyond the basics of art appreciation. We will deconstruct the tools a curator uses to build a visual argument. You will learn to identify the narrative being told through the strategic arrangement of artworks, understand how lighting is engineered to provoke specific feelings, and ultimately, grasp the difference between a collection of objects and a masterfully curated thesis. This is not about having the “right” opinion; it’s about developing the discerning eye to understand how that opinion was shaped for you.

To truly grasp the art of exhibition critique, it’s essential to understand its distinct components. This article will guide you through the core principles, from decoding the curatorial narrative to mastering the practicalities of an optimal visit, enabling you to transform your gallery walks into profound analytical exercises.

Summary: A Professional’s Guide to Exhibition Critique

- How to Read the Story a Curator Is Telling Through Piece Placement?

- Spotlight vs Ambient: How Lighting Manipulates Your Emotional Response to Art?

- Retrospective or Group Show: Which Offers Better Insight into an Era?

- The Mistake of Reading the Plaque Before Looking at the Artwork

- When to Visit Blockbuster Exhibitions to Avoid the “Cattle Drive” Experience?

- Sanatorium or Theme Park: Which Offers Better Atmospheric Lighting?

- Guide vs Solo: Which Method Best Reveals the Social Nuances of a Region?

- How Authentic Cultural Immersion Develops Critical Soft Skills for Global Professionals?

How to Read the Story a Curator Is Telling Through Piece Placement?

An exhibition is not a random assortment of beautiful objects; it is a meticulously constructed text. A curator uses artworks as words and the gallery space as a page to compose a visual argument. Your first task as a critic is to stop seeing individual pieces and start reading the sentences they form together. Look for the “silent dialogue” between adjacent works. Does a modern sculpture’s form echo the lines of a classical painting across the room? Does the juxtaposition of two pieces create irony, harmony, or a sense of conflict?

The sequencing of an exhibition, its pacing, is a primary narrative tool. Pay attention to sightlines—the specific views the curator has framed for you as you move through the space. Often, a piece you see in the distance from one room is designed to be a visual anchor or a question that will be answered as you advance. The flow from a small, intimate gallery into a large, overwhelming one is a deliberate emotional manipulation designed to affect your interpretation of the art contained within.

Case Study: The Chrono-Thematic Grammar of James Barnor at the Serpentine

The James Barnor retrospective was a masterclass in curatorial grammar. Rather than a simple chronological walk-through, the layout was thematic. As visitors moved through the space, they witnessed the parallel transformations of Accra and London from the 1950s to the 1980s. The curator used strategic sightlines to create “visual echoes” between portraits taken in a colonial context and those from a post-colonial era, forcing a silent, powerful conversation about identity, migration, and history. The placement itself told a story that was richer than any single photograph could convey.

Ultimately, a successful critique identifies this curatorial intent. Ask yourself: what is the central thesis of this show? Is it a historical argument, a political statement, a formal exploration? The arrangement of the pieces is your primary clue. It is the syntax of the exhibition’s unspoken language.

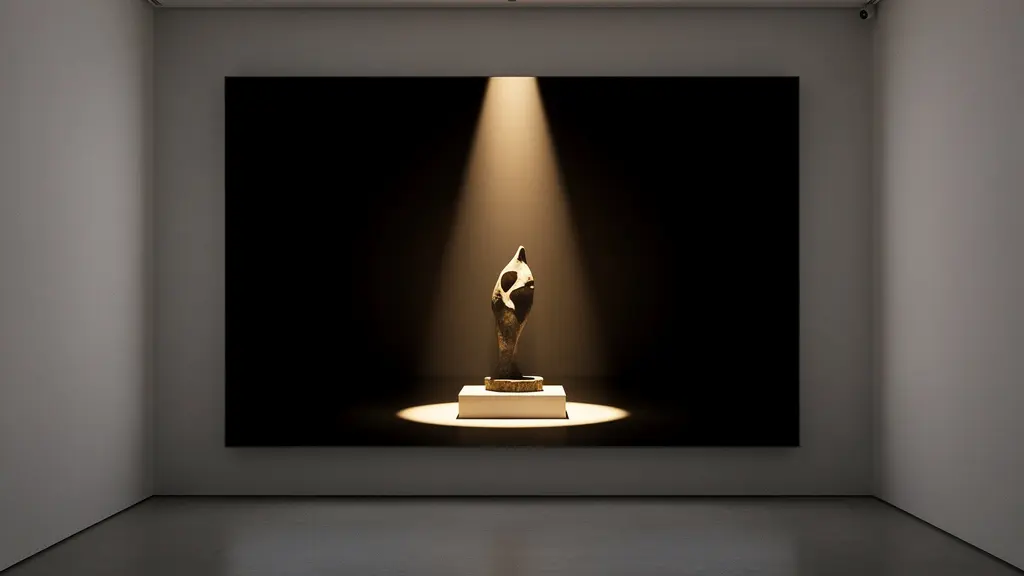

Spotlight vs Ambient: How Lighting Manipulates Your Emotional Response to Art?

Lighting in a gallery is never a neutral utility; it is arguably the curator’s most potent tool for emotional and psychological manipulation. It directs your eye, sets the mood, and fundamentally alters your perception of form, color, and texture. A professional critic must learn to see light not just as illumination, but as an active participant in the exhibition’s narrative. Distinguishing between different lighting strategies is the first step.

The two most common approaches are spotlighting and ambient lighting. Spotlighting, with its high contrast and focused beams, creates drama, intimacy, and a sense of theatrical importance. It isolates an artwork from its surroundings, demanding singular focus and often invoking a feeling of reverence. Conversely, ambient lighting provides a broad, even wash of light that reduces contrast and promotes a more contemplative, intellectual viewing experience. It allows artworks to be seen in relation to one another within the architectural space.

The choice between these is a critical curatorial decision. This image below perfectly illustrates the duality: a sculpture is given theatrical weight with a dramatic spotlight, while the paintings on the wall are presented in a calm, even ambient light, inviting a different kind of viewing.

As you can see, the intense spotlight creates a chiaroscuro effect on the sculpture, heightening its three-dimensionality and emotional impact. The surrounding pieces, bathed in softer light, recede, allowing for a quieter, more holistic assessment. This is not an accident; it’s a directorial choice that tells you how to feel about each work. The temperature of the light itself is another layer of this manipulation, with warmer tones often used to evoke nostalgia and cooler tones to create a more clinical or modern feel.

Retrospective or Group Show: Which Offers Better Insight into an Era?

The format of an exhibition—primarily the choice between a solo retrospective and a group show—dictates the type of insight a visitor can gain. Neither is inherently superior, but they serve fundamentally different purposes, and a discerning critic must adjust their analytical lens accordingly. A retrospective offers depth, while a group show provides breadth. The question is not which is better, but what each format uniquely reveals about an artist or an era.

A retrospective is a deep dive into a single artist’s career. It allows you to trace their evolution, identify recurring themes, and witness the development of their technique and vision over time. It presents a coherent, focused narrative, often constructed with the artist’s own involvement. However, this focus can also be a limitation, presenting a singular, sometimes self-mythologizing, perspective. In fact, recent museum attendance studies reveal that while 73% of visitors prefer retrospectives for understanding an artist, they may offer a narrower view of the period.

A group show, on the other hand, functions as a conversation. It places multiple artists in dialogue, revealing the key debates, aesthetic alliances, and conceptual rivalries of a particular time or movement. It sacrifices individual depth to map a broader cultural landscape. As critic and curator Sarah Urist Green notes, this format offers a more complex, and often more honest, picture of an era:

Retrospectives provide unparalleled depth into one artist’s evolution, but it’s a single, often self-mythologizing, voice. Group shows reveal the era’s key debates, alliances, and rivalries, offering breadth at the expense of individual depth.

– Sarah Urist Green, The Art Assignment – Curatorial Perspectives

A professional critique of a group show, therefore, should focus less on the merits of individual works and more on the quality of the conversation the curator has orchestrated. Does the selection of artists feel predictable or revelatory? Do the juxtapositions create new insights or simply state the obvious? Evaluating the success of this curatorial argument is the core task.

The Mistake of Reading the Plaque Before Looking at the Artwork

One of the most common and detrimental habits of the amateur gallery-goer is the immediate beeline for the wall plaque, or “didactic.” This act, while seeming diligent, is a critical error. It short-circuits your own perceptual and emotional response, replacing it with a pre-packaged, institutional interpretation. Reading the text first tells you what to think and feel, preventing the artwork from speaking for itself. A professional critic understands that their primary data is their own unmediated encounter with the art.

The text on the wall is not an objective truth; it is a piece of writing with its own agenda. It can be promotional, overly academic, or intentionally poetic. It often omits controversies, simplifies complex ideas, and frames the work within a narrative that serves the museum’s goals. To critique an exhibition effectively, you must first form your own thesis based on visual evidence alone. Only then can you critically engage with the provided text and analyze its purpose. Does it illuminate or obscure? Does it confirm your interpretation or contradict it? The gap between your experience and the gallery’s explanation is often where the most interesting critique lies.

To cultivate this essential skill, adopt the “Two-Pass System.” This structured approach ensures you privilege your own experience before engaging with the curator’s explicit narrative, transforming you from a passive consumer of information into an active analyst.

Action Plan: The Two-Pass System for Professional Art Critique

- First Pass (The Emotional Read): Walk through the entire exhibition without reading a single plaque or wall text. Let your intuition guide you. Make mental or physical notes of which pieces draw you in, which ones repel you, and the immediate feelings or thoughts they provoke.

- Document Initial Impressions: After the first pass, pause and document your raw reactions. Which visual pathways did you follow? What was the overall emotional arc of the show? This is your untainted qualitative data.

- Second Pass (The Analytical Read): Now, walk through the exhibition again, this time reading the plaques for the pieces you noted. Approach the text with a critical eye. Does the information confirm, contradict, or enrich your initial interpretation?

- Analyze the Plaque’s Voice: Determine the tone of the text. Is it academic, promotional, historical, or poetic? Who is speaking, and what perspective does this voice represent? This helps you understand the institution’s framing.

- Identify Omissions: The most advanced step is to note what is *not* said. Are there challenging political aspects, controversial materials, or critical failures in the artist’s history that are conspicuously absent from the text? These omissions are a curatorial choice in themselves.

By treating the wall text as another layer to be analyzed rather than a manual to be followed, you empower yourself to form a genuinely independent and sophisticated critique of both the art and its presentation.

When to Visit Blockbuster Exhibitions to Avoid the “Cattle Drive” Experience?

The ability to engage in a deep critique is directly proportional to the quality of your viewing experience. It’s nearly impossible to have a meaningful connection with an artwork when you are jostled by crowds, rushed by guards, and viewing pieces over a sea of smartphone screens. The “blockbuster” exhibition, while a testament to an artist’s popularity, often creates the worst possible environment for serious analysis. A professional knows that timing is everything.

Avoiding the “cattle drive” experience requires strategic planning. The opening and closing weeks of any major exhibition are invariably the most crowded, fueled by initial hype and last-chance urgency. The sweet spot for an optimal visit lies in the middle of the show’s run. In-depth, comprehensive visitor flow analysis demonstrates that the “Mid-Run Lull”—typically weeks four through eight of a twelve-week exhibition—can see up to a 65% reduction in crowd density. This is your prime opportunity for a contemplative visit.

Beyond the week, the time of day is your next strategic lever. The first hour of opening is often packed with eager visitors. The most serene and valuable time for viewing is almost always the last 60-90 minutes of a weekday’s operating hours. The same data shows that this period often has 70% fewer visitors than the morning rush. The galleries begin to empty, the light often softens, and the space returns to a state where personal reflection is possible. It is in this quiet that you can truly practice the observational skills discussed, tracing sightlines and feeling the atmospheric effects of the lighting without distraction. A quiet gallery is a prerequisite for a thoughtful critique.

Sanatorium or Theme Park: Which Offers Better Atmospheric Lighting?

Moving beyond the simple distinction between spotlight and ambient, a professional critic develops a vocabulary to describe overarching lighting philosophies. Two of the most useful archetypes are the “Sanatorium” and the “Theme Park.” Recognizing which philosophy a curator has employed—and whether it is appropriate for the art on display—is a hallmark of a sophisticated critique. The goal isn’t to decide which is “better” in a vacuum, but which is more effective for the specific works in the show.

The “Sanatorium” style, often called “white cube” lighting, prioritizes even, diffuse, bright, and often cool-toned illumination. It aims for clinical clarity and neutrality. The goal is to eliminate shadows and create an environment where the artwork can be examined with minimal atmospheric interference. This approach is highly effective for conceptual art, minimalist works, and text-based pieces where intellectual engagement is paramount. It treats the gallery as a laboratory for ideas.

The “Theme Park” style is the opposite. It embraces high-contrast, dramatic, directional, and sometimes colored light to create an immersive, emotional, and theatrical experience. It uses shadow as an active element and is less concerned with “truthful” color representation than with creating a powerful mood. This is ideal for large-scale installations, dramatic sculptures, and emotional figurative works where the desired response is visceral rather than purely intellectual. The gallery becomes a stage.

| Lighting Style | Characteristics | Best For | Avoid For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sanatorium | Even, diffuse, bright, cool-toned | Conceptual art, minimalism, text-based works | Baroque paintings, dramatic sculptures |

| Theme Park | High-contrast, dramatic, directional, colored | Large installations, emotional figurative works | Delicate drawings, archival documents |

| Studio Lighting | Replicates artist’s working conditions | Understanding artistic process and intention | Contemporary digital art |

The ultimate sign of a curatorial misstep is a mismatch between the art and the lighting philosophy. As noted by the *Museum Lighting Design Quarterly*, “When ‘Sanatorium’ lighting makes dramatic art feel flat, or when ‘Theme Park’ lighting makes conceptual art feel gimmicky, it reveals a fundamental curatorial misstep in understanding the work’s essential nature.” Identifying this dissonance is a high-level critical act.

Guide vs Solo: Which Method Best Reveals the Social Nuances of a Region?

When an exhibition’s goal is to offer insight into the social or cultural nuances of a place, the method of your visit—whether with a guide or solo—dramatically impacts the information you absorb. Neither is a perfect method, but understanding their respective biases is crucial for a well-rounded critique. A guided tour provides the official, institutional narrative, while a solo visit allows for personal interpretation, but may miss crucial context.

Docent-led tours are invaluable for accessing the curator’s intended message. They are trained to deliver a polished, coherent narrative that highlights key works and explains the overarching themes of the show. However, this narrative is, by definition, a sanctioned one. It often smooths over complexities and presents a single, authoritative interpretation. A study comparing different visit types at major museums was revealing: it found that solo visitors typically absorbed only 40% of the intended curatorial message, while docent-led groups understood 75%. The most telling finding, however, was that tours led by the artists or curators themselves revealed 90% more personal and controversial context—details often omitted from official presentations.

For the solo visitor aiming for a deeper understanding, a powerful “insider” technique is that of the “Eavesdropping Ethnographer.” Instead of joining a single tour, position yourself strategically to overhear snippets from multiple different guided tours as they pass through the galleries. You will quickly notice variations between docent scripts, discover which artworks elicit the most spontaneous visitor reactions, and hear the questions that the official narrative fails to answer. This method allows you to compare the institutional story with the public’s reception of it, synthesizing a much richer, multi-layered understanding of the exhibition’s social resonance. You are not just critiquing the show, but also its reception and its place in a public dialogue.

A truly comprehensive critique often requires both: a solo pass to form an independent thesis, and a guided tour (or strategic eavesdropping) to understand the official narrative you are critiquing against. The tension between these two perspectives is where deep insight is born.

Key Takeaways

- The highest form of critique is not of the art, but of the exhibition’s “visual argument” constructed by the curator.

- Lighting and placement are not functional afterthoughts; they are primary rhetorical tools designed to direct your focus and manipulate your emotional response.

- Adopt the “Two-Pass System”: form your own emotional and visual interpretation first, before critically engaging with the institution’s textual narrative.

How Authentic Cultural Immersion Develops Critical Soft Skills for Global Professionals?

The practice of critiquing an art exhibition, when approached with professional rigor, transcends a mere hobby. It is a powerful form of cognitive training that develops critical soft skills directly applicable to the world of global business and complex problem-solving. The gallery, in this sense, becomes a gymnasium for the mind, where the muscles of observation, interpretation, and synthesis are honed. The act of decoding a visual argument is a direct parallel to navigating ambiguous, cross-cultural business environments.

When you engage with an artwork from a different culture without the crutch of explanatory text, you are forced to exercise a specific kind of intellectual humility. You must observe carefully, recognize the limits of your own perspective, and build a hypothesis based on incomplete information. This process is what Dr. Del Barrett calls “Visual Empathy Training.” In her work on “Cultural Intelligence Through Art Analysis,” she argues that “The act of decoding an artwork without text is an exercise in understanding a different perspective, value system, and emotional language—a direct parallel to cross-cultural communication in global business.”

Gallery critique as ‘Visual Empathy Training’: The act of decoding an artwork without text is an exercise in understanding a different perspective, value system, and emotional language—a direct parallel to cross-cultural communication in global business.

– Dr. Del Barrett, Cultural Intelligence Through Art Analysis

This is not a theoretical benefit. The connection between art engagement and executive function is increasingly documented. A landmark Harvard Business Review study found that 82% of global executives who regularly engage in art criticism report improved cross-cultural negotiation skills and an enhanced ability to navigate ambiguous business situations. By learning to “read” a gallery, they are simultaneously learning to read a boardroom, to spot the unspoken message, and to appreciate the nuances of a perspective different from their own.

Therefore, your next trip to a museum is more than just a cultural outing; it is an opportunity for professional development. It is a chance to practice seeing the world through another’s eyes, to build an argument from visual data, and to become more comfortable with the ambiguity that defines both great art and global leadership.

The next time you walk into a gallery, leave the desire for simple judgments at the door. Instead, arm yourself with these observational tools and approach the exhibition as a complex text waiting to be decoded. Your reward will be a richer, more profound understanding of not only art, but of the very nature of communication itself.