Contemporary art’s value doesn’t come from the object itself, but from the cultural performance it generates—a shift that leaves traditional, object-focused collectors confused.

- An artwork’s price is often determined by the discourse, controversy, and conceptual narrative it creates, not by the artist’s technical skill alone.

- Digital works like NFTs and ephemeral acts like Banksy’s shredded painting derive their aura and worth from manufactured scarcity and the power of the event.

Recommendation: To understand contemporary art, stop judging the object and start critiquing the performance. Analyze the story, the context, and the system the artwork is commenting on.

For the enthusiast steeped in the traditions of Rembrandt’s chiaroscuro or the sublime landscapes of Turner, the contemporary art world can feel like a disorienting, alien territory. An unmade bed, a shark in formaldehyde, or a banana duct-taped to a wall are not just questioned as “art,” but their astronomical price tags are met with a mix of disbelief and indignation. The common refrain, “My child could have done that,” isn’t just a critique of technical skill; it’s a fundamental misunderstanding of the currency in which contemporary value is traded.

Many attempts to bridge this gap fall into familiar platitudes, urging viewers to “read the wall text” or accept that “it’s all about the concept.” While true, these explanations are incomplete. They fail to articulate the seismic shift in the very mechanics of value creation. The confusion arises from applying an old rulebook—one that values material, craft, and aesthetic beauty—to a new game. This new game is not played on the canvas alone; it’s a performance played out in auction houses, on social media, and in the global consciousness.

The key to decoding contemporary art is to shift our perspective. We must move from seeing the artwork as a static, self-contained object of value to understanding it as a token of a performance. The art object is often merely a relic of a larger event, a conversation starter, or a node in a complex network of ideas. Its value is not inherent in its physical form but is generated by the performance it initiates, the systems it critiques, and the attention it commands.

This guide will deconstruct this performance-based value system. By examining iconic and perplexing examples of contemporary expression, we will build a new framework for analysis, allowing you to move from confusion to critical understanding and appreciate the provocative, challenging, and often brilliant game being played.

Summary: Decoding Contemporary Artistic Expression

- Why a Banana Taped to a Wall Is Valued at $120,000?

- NFTs vs Physical Canvas: Can Digital Files Carry True Artistic Aura?

- How Banksy Changed the Rules of Street Art Monetization?

- The “Interactive” Art Trap That Relies on Your Selfie to Exist

- How to Spot Emerging Artists Before They Are Signed by Mega-Galleries?

- Why the NSA Spy Station in Berlin Is Now a Street Art Gallery?

- Why Generative AI Fails to Replicate Brand Voice in Emotional Campaigns?

- Curated Exhibitions: How to Critique a Gallery Show Like a Professional?

Why a Banana Taped to a Wall Is Valued at $120,000?

Maurizio Cattelan’s *Comedian* (2019) is the quintessential example of an artwork whose value is entirely divorced from its material composition. The piece—a fresh banana duct-taped to a gallery wall—is not about the banana. It is a work of institutional critique and a masterclass in generating value through performance. The initial $120,000 price was not for the fruit, but for a certificate of authenticity and instructions, allowing the owner to replace the banana as it rots. The value resides in the ownership of the concept, not the object.

The true artistic medium here is the art market itself. As Cattelan stated in a Contemporary Art Issue interview, “If I had to be at a fair, I could sell a banana like others sell their paintings. I could play within the system but with my rules.” The artwork’s genius lies in its ability to expose the absurdity and arbitrariness of how value is assigned in the art world. It’s a joke that everyone, especially the collectors who buy it, is in on. The performance is the global media frenzy, the debates it sparks, and the ultimate proof of its own thesis when it sells.

Case Study: The Performance of Consumption

The concept of “value as performance” was perfectly demonstrated when cryptocurrency entrepreneur Justin Sun purchased a version of *Comedian*. In a live event, he ate the banana, stating the act “can also become a part of the artwork’s history.” This act did not destroy the art; it completed it. It proved the physical object was irrelevant. The true artwork was the concept, the media event, and the discourse it generated. In fact, this performance only amplified its worth; another version of the work later saw its value skyrocket, as a recent report shows the artwork’s value skyrocketed to $6.24 million in a 2024 auction. The art is not the banana; it’s the entire, absurd, and brilliant story.

From a traditional perspective, this is nonsensical. But viewed as performance, the banana is merely a prop. The real work is the conversation about value, celebrity, and the mechanisms of the art market that Cattelan successfully orchestrated on a global scale. The collector buys a ticket to be part of that historic performance.

NFTs vs Physical Canvas: Can Digital Files Carry True Artistic Aura?

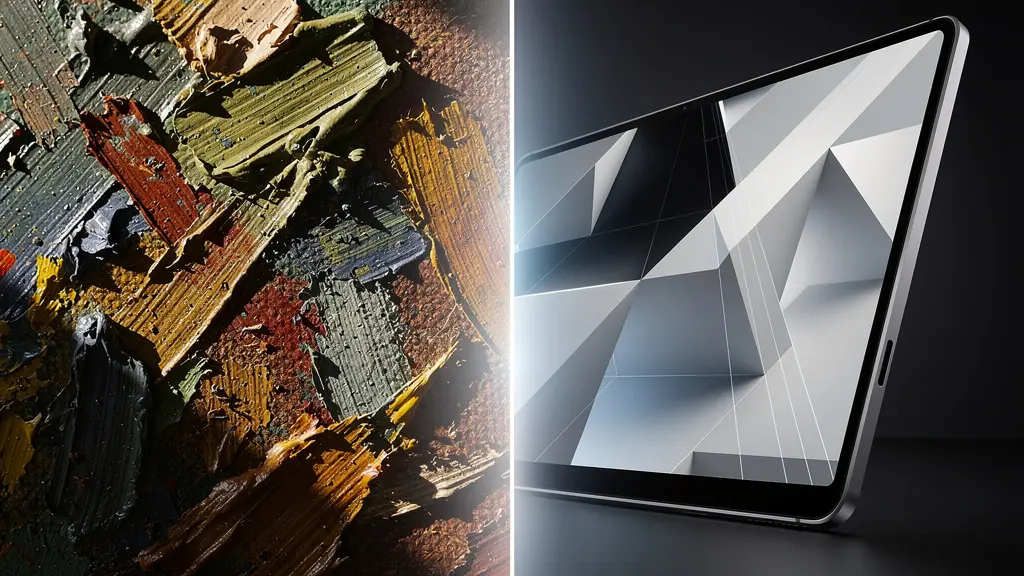

The debate over Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) strikes at the heart of what gives an artwork its “aura”—a term coined by Walter Benjamin to describe the unique presence of an original work of art in time and space. For traditional collectors, this aura is tied to the physical object: the texture of paint on canvas, the chisel marks in marble. A digital file, infinitely reproducible, seems to lack this essential quality. How can a JPEG have the same gravitas as a Rembrandt?

The answer lies in a modern re-engineering of scarcity and provenance. NFTs do not make the digital file unique; they make the *ownership* of it unique through the public, unchangeable ledger of the blockchain. This technology creates a new kind of digital aura. It’s not an aura of physical presence but one of verifiable authenticity and lineage. The value is transferred from the physical to the cryptographic. This is a profound shift, creating an ecosystem where the digital art ecosystem reached a $5 billion valuation on the Ethereum blockchain alone by 2024.

As the image above contrasts, the tactile, material history of a painting is replaced by a transparent, digital history on the blockchain. The Chromie Squiggle collection by Snowfro is a prime example. These simple, algorithmically generated lines have become blue-chip assets, with a Statista report showing Chromie Squiggle leading NFT art collections with a market cap of $238 million. Their value comes not from the visual complexity but from their status as one of the first and most influential generative art projects on the Ethereum blockchain. Owning one is like owning a piece of digital art history.

For a traditional collector, this means learning a new language of value. The questions are no longer about brushstrokes and patina but about smart contracts, community significance, and the historical importance of a project within the rapidly evolving digital landscape. The aura has not disappeared; it has simply been coded.

How Banksy Changed the Rules of Street Art Monetization?

Banksy operates as a masterful paradox: an anti-capitalist artist who has become a global brand worth hundreds of millions. His genius lies in subverting the traditional gallery system while simultaneously creating a highly controlled, alternative market for his work. He didn’t just put art on the street; he transformed the street into a gallery and the subsequent media frenzy into his auction room. This represents a monetization strategy built on political performance and controlled scarcity.

Unlike street artists before him whose work was ephemeral and legally ownerless, Banksy created a system to capture the value of his public interventions. His most powerful tool is Pest Control, the only official body that can authenticate his works. This organization acts like a high-end gallery’s verification service, creating an official market for what was once a transient, illegal act. A stencil on a wall is public property, but a print of that stencil, authenticated by Pest Control, becomes a coveted collector’s item—a “relic of the discourse” that Banksy initiated in public.

Perhaps his most famous performance was the 2018 shredding of *Girl with Balloon* moments after it was sold for $1.4 million at Sotheby’s. This act of apparent self-destruction was, in reality, an act of supreme value creation. The performance generated worldwide headlines and transformed the painting into a new piece, *Love is in the Bin*, with a story and historical significance that made it far more valuable. It wasn’t the image that mattered anymore; it was the audacious event of its partial destruction. The performance became the art.

Action Plan: Deconstructing the Banksy Effect

- Authentication as Exclusivity: Analyze how the Pest Control system mimics the exclusivity and gatekeeping of traditional mega-galleries to create scarcity and certify value.

- Event-Driven Value: Identify how public interventions are timed to create collectible “relics” of specific political moments, turning news cycles into market demand.

- Performative Destruction: Examine the use of performative acts, like the shredding of *Girl with Balloon*, as a strategy to exponentially increase an artwork’s narrative value and price.

- Branded Anonymity: Deconstruct how maintaining anonymity while building a globally recognizable artistic style creates a powerful, mysterious brand that fuels speculation.

- Media Amplification: Track how controversy and media cycles are deliberately leveraged to amplify an artwork’s significance and, consequently, its market value, as confirmed by analyses of today’s most controversial artworks.

The “Interactive” Art Trap That Relies on Your Selfie to Exist

The rise of social media has spawned a new genre of art experience, often labeled “interactive” or “immersive.” These are the kaleidoscopic ball pits, neon-lit angel wing murals, and infinity mirror rooms that seem designed less for contemplation and more for Instagram. For traditionalists, this can feel like the ultimate hollowing-out of artistic intent, where aesthetic experience is reduced to a photogenic backdrop for a selfie. This phenomenon highlights a crucial distinction in the contemporary art world: the difference between genuine interactive art and installations built for the attention economy.

Genuine interactive art, in the tradition of artists like Yayoi Kusama or Olafur Eliasson, uses the viewer’s presence to complete a perceptual or psychological concept. The viewer is a participant in an experience designed to alter their sense of space, self, or reality. In contrast, “Instagram museums” reverse this dynamic: the artwork is an inert stage, and the viewer becomes the primary content creator and distributor. The art’s existence is validated not by individual experience but by its viral spread across social networks. The selfie is not a byproduct of the experience; it *is* the experience.

This table clarifies the fundamental differences in intent and value creation between these two models.

| Aspect | Instagram Museums | Genuine Interactive Art (Kusama, Eliasson) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Intent | Social media engagement | Perceptual/psychological experience |

| Artistic Depth | Surface-level aesthetics | Conceptual and sensory exploration |

| Viewer Role | Content creator/distributor | Active participant in meaning-making |

| Value Creation | Through viral shares and likes | Through individual contemplation |

| Longevity | Trend-dependent, ephemeral | Museum collection worthy |

This isn’t to say that art made for social media is inherently “bad,” but it operates on a different value system. Its success is measured in likes, shares, and user-generated content, not in its contribution to art history or its conceptual depth. For the discerning collector, the challenge is to distinguish between works that leverage the viewer for a profound artistic purpose and those that simply leverage them for free marketing.

How to Spot Emerging Artists Before They Are Signed by Mega-Galleries?

For the collector who wants to move beyond established names, identifying the next significant artist is the ultimate challenge. In a world saturated with MFA graduates and Instagram artists, the signal-to-noise ratio is overwhelming. Relying on traditional markers of quality, like technical skill, is no longer sufficient. To spot emerging talent today, one must learn to read the subtle signals of the art world’s ecosystem, looking for artists who are generating critical discourse long before they generate significant sales.

Mega-galleries like Gagosian or Zwirner often sign artists who have already built a substantial foundation of institutional and critical support. The key is to spot this foundation as it’s being built. This involves looking beyond the art itself and analyzing the network and conversation surrounding the artist. An artist with a raw, challenging practice but who is being included in shows by respected independent curators or is acquired by a known “tastemaker” private collector is a much stronger signal than an artist with a polished aesthetic but no critical engagement.

This process is akin to being a cultural detective, piecing together clues that point toward future significance. The goal is to identify artists who are not just making objects, but are contributing a new and necessary voice to the broader artistic conversation. Below are key indicators that an artist is on a serious upward trajectory, often before their market value has caught up, based on methods used by leading contemporary collectors.

- Prestigious Residency Participation: Track inclusion in non-mainstream but highly respected residency programs known for fostering critical work.

- “Tastemaker” Curator Inclusion: Monitor group shows curated by independent curators known for their forward-thinking and institution-challenging perspectives.

- Academic and Critical Citation: Analyze how frequently the artist is cited in niche art journals, academic papers, and critical essays, even if popular press is absent.

- Strategic Social Network: Map the artist’s connections to established artists, critics, and junior curators at major institutions, as these often act as early advocates.

- Early Collection Acquisition: Watch for acquisitions by known, forward-thinking private collections, which often move faster and take more risks than large museums.

- High “Discourse Velocity”: Measure the frequency and depth of critical discussion around the artist’s work, even in the absence of high sales figures.

Why the NSA Spy Station in Berlin Is Now a Street Art Gallery?

The transformation of Teufelsberg (“Devil’s Mountain”) in Berlin from an abandoned US National Security Agency listening post into one of the world’s largest street art galleries is a powerful metaphor for value creation through recontextualization. The art at Teufelsberg—ranging from simple tags to vast, elaborate murals—derives its profound meaning not just from its aesthetic qualities, but from its direct dialogue with the history and architecture of the site. The location itself imbues the art with a specific political and historical aura.

A graffiti tag on a pristine suburban wall is vandalism. That same tag on the decaying dome of a Cold War spy station becomes a statement about the fall of empires, the reclamation of power, and the triumph of individual expression over state surveillance. The artists are not just painting on a surface; they are painting on a layer of history. This act of artistic appropriation radically alters the meaning of both the art and the site.

Case Study: The Aura of Teufelsberg

The site’s history is the invisible medium every artist there uses. As detailed in an essay by Deliberatio, Teufelsberg exemplifies art’s capacity for radical recontextualization. Once a symbol of covert power and international tension, its transformation into an anarchic, open-air canvas is a potent performance. Visitors come not just to see murals, but to experience the frisson of standing in a place where history was made, now overwritten by a new, vibrant, and chaotic narrative. The decay of the architecture and the vibrant life of the art create a palpable tension that is the core of the Teufelsberg experience. The value here is entirely contextual.

This principle of recontextualization is a key tool in the contemporary artist’s arsenal. By placing an object or an act in an unexpected context, the artist forces the viewer to see it anew. It could be a piece of street art on a spy station or, returning to our first example, a banana in a prestigious art fair. In both cases, the location and context are not passive backdrops; they are active participants in the creation of the artwork’s meaning and value.

Why Generative AI Fails to Replicate Brand Voice in Emotional Campaigns?

As generative AI tools become increasingly sophisticated, they can produce visually stunning and textually coherent outputs. They can mimic styles, combine concepts, and generate endless variations. Yet, they consistently fail at one crucial task: replicating the authentic emotional resonance of a powerful artistic or brand voice. This failure reveals a fundamental truth about what we value in human expression: the perceived intent and lived experience behind the work.

AI operates on patterns, probabilities, and vast datasets of existing human creation. It can assemble a statistically likely representation of “sadness” or “joy,” but it cannot have an authentic stake in those emotions. It has no personal history, no vulnerabilities, and no genuine perspective on the world. The resulting work often feels hollow, a technically proficient but soulless collage of human feeling. True emotional connection in art comes from the viewer’s belief that they are witnessing a genuine expression of another consciousness.

The artist’s role is not merely to create an aesthetic object, but to interpret reality through a unique, subjective lens. As Maurizio Cattelan powerfully states, “I actually think that reality is far more provocative than my art. I just take it; I’m always borrowing pieces—crumbs really—of everyday reality.” This act of “borrowing”—of selecting, framing, and commenting on the world—is an act of human agency that AI cannot replicate. An AI can generate a picture of a banana, but it cannot conceive of the performance of taping it to a wall at an art fair to critique the art market.

This is why AI struggles with emotional brand campaigns. A brand’s voice is its personality, its values, its story. It is built through a series of consistent, intentional choices. While AI can generate ad copy, it cannot originate the core belief system that makes a brand’s message resonate on an emotional level. The “art” of creation, whether for a gallery or a campaign, lies not in the final product but in the human intentionality that animates it.

Key Takeaways

- Contemporary art’s value is often created through “performance”—the discourse, context, and concept—not the physical object.

- Digital art like NFTs achieves its “aura” and value through cryptographically-verified scarcity and historical significance on the blockchain.

- To spot emerging talent, focus on an artist’s critical engagement and network (curators, residencies) rather than just sales or aesthetics.

Curated Exhibitions: How to Critique a Gallery Show Like a Professional?

Walking into a gallery and critiquing a show involves more than simply deciding which individual pieces you “like.” A professional critic or a savvy collector analyzes the exhibition as a whole, as a cohesive statement. The most important element in this analysis is understanding the curatorial thesis. The curator is not just a decorator who hangs pictures; they are an author who uses artworks as their words and the gallery space as their page to construct an argument.

To critique a show like a professional, your first task is to identify this argument. What conversation is the curator trying to start? How do the chosen works speak to each other? Does a dialogue emerge from their juxtaposition, or do they feel like a random assortment? Sometimes the thesis is explicit, stated in the exhibition text. Other times, it’s implicit, and you must deduce it from the selection, arrangement, lighting, and flow of the space. A great exhibition is one where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, and that “greater” element is the strength and originality of the curatorial thesis.

This requires a form of connoisseurship that goes beyond just identifying an artist’s style. As Oliver Miro of the V&A noted during an Art Business Conference panel, “Of course connoisseurship is important for contemporary art! It means really understanding the artists that we represent, understanding everything about them and the context for their work.” This deep knowledge is precisely what’s needed to evaluate not just the art, but the curator’s use of that art to build their argument. The exhibition itself becomes a work of art to be critiqued.

Ultimately, a professional critique assesses the success of this curatorial performance. Did the curator present a fresh perspective? Did the selected artworks effectively support the thesis? Did the exhibition’s design enhance or detract from the argument? By asking these questions, you move beyond personal taste and engage with the exhibition on an intellectual and critical level, just as you would with a scholarly text or a complex film.

Frequently Asked Questions About Contemporary Art

How do you assess the curator’s thesis in an exhibition?

Look for the coherence and originality of the curator’s argument as expressed through artwork selection and arrangement. A strong curatorial thesis should be evident in how pieces dialogue with each other.

What role does gallery architecture play in critique?

The building’s architecture influences viewer experience significantly. Consider how spatial flow, lighting, and architectural features either support or compete with the artworks’ intended impact.

How do you identify institutional agendas in exhibitions?

Examine funding sources, the gallery’s commercial relationships, and any political or social positioning. These factors often shape what is shown and how it’s presented, affecting the exhibition’s underlying message.